SNIFFING OUT COVID

Doctors and researchers are training dogs to detect if people are infected.

By FRANCES STEAD SELLERS Washington Post

Blaze’s success also marks an advance in the evolving field of olfactory disease detection — the concept that many illnesses, including emerging diseases, are characterized by distinct “odorprints” that can be identified by both dogs and artificial noses, which could be quicker, less invasive and more accurate than current clinical testing.

| “This is a major field of research worldwide,” said Kenneth Suslick, a professor of chemistry at the University of Illinois. Still, scientists are emphasizing the need to proceed with caution. “As eager as we are to put this out there, we want to make sure it is responsible, ethical, scientific and safe,” Otto said. “Done wrong, it could be more damaging than helpful.” Perdita Barran, a professor at the University of Manchester , also note that training dogs is time-consuming and expensive. “It doesn’t scale with the cost of dogs.” |

| The Penn team’s research, funded largely by private donations, is based on two established principles: that changes in our health often alter the way we smell; and that dogs, with 50 times as many smell receptors as people, make great biosensors with a proven ability to detect not only drugs and explosives but some diseases, such as hidden cancers; sudden shifts in blood sugar levels and parasitic, bacterial and viral infections. The work, which draws on disciplines including neuroscience, chemistry, nanotechnology and animal cognition, also reveals how much we still don’t know about the way the sense of smell works. |

There’s nothing new about the notion that diseases smell. In his aphorisms, written in 400 B.C., Hippocrates, the “father of modern medicine,” recognized a “heavy smell” in people suffering from certain illnesses. A sudden change in the way our breath or urine smells remains a reason to see a doctor.

That’s because human bodies constantly give off a cocktail of chemicals known as volatile organic compounds, or VOCs, in sweat, saliva, urine, breath and sebum that change when cells grow, as in the case of cancer, or when they die after being infected, for example, by a virus.

“With covid detection, you are not recognizing the virus,” Suslick said. “You are recognizing the volatile byproducts of cells dying because they have been infected.”

Several mysteries hover over the work at the training facility. “We don’t know what the dogs are finding, what the common denominator is,” Otto said.

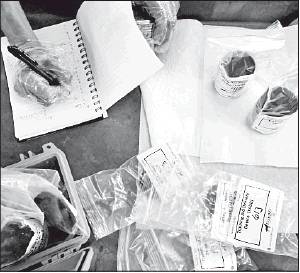

The researchers have been changing the positive samples they are using as the work evolves. In early July, they were working with chemically deactivated urine. The dogs were later presented with heat-treated urine, as well as other secretions collected from T-shirts worn by recently tested people, some of whom have the coronavirus but are not sick enough to be hospitalized.

Despite distractions in one session, the trainees performed with stunning accuracy until one Labrador froze in front of a can containing a urine sample from a hospitalized patient who had tested negative for the virus.

It was one of the few mistakes of the day. Unless it wasn’t a mistake. Clinical tests give more than 10% false negative results and “the dogs may be better than the tests,” Nolan said.

That appeared to be true a few weeks later, when the dogs all alerted on a sample from a patient who had tested negative. They were so insistent — and consistent — that Otto went back to the hospital to learn more about the person’s history. It turned out the patient had previously tested positive, suggesting there may have been some lingering odor from the earlier infection.

“There’s a phrase in dog training,” Otto said: “Trust your dog.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed