For decades, the attitude of unions and their advocates to increased automation could be summed up in one word: no. They feared that every time a machine was put into the workflow, a laborer lost a job.

The pandemic has forced a shift in that calculation. Because human contact spreads the disease, some machines are now viewed not exclusively as the workers’ enemy but also as their protector. That has accelerated the use of robots this year in a way no one expects to stop.

“If you keep me 6 feet away from the other worker and you have a robot in between, it’s now safe,” said Richard Freeman, a professor of economics at Harvard University. “The unions aren’t going to say, ‘No, you should have the workers standing next to each other so they get sick.’ ”

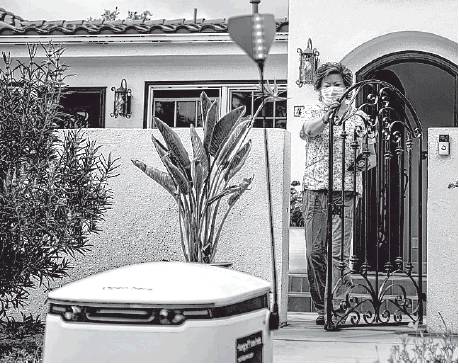

The result is the spread of windshield-mounted toll detectors, automated floor cleaners at factories, salad-chopping machines in grocery stores, mechanical butlers at hotels and electronic receipts for road pavers. What remains less clear is where the men and women who used to do some of those jobs will work.

The impact of technology on employment has been a topic of anxiety and study for generations. Cars didn’t kill trains, television didn’t end radio. When banks installed ATMs, they hired more people, not fewer, because the variety of their services grew. Still, machines have eliminated many jobs, and the current wave is likely to be no exception. “When we come out of this crisis and labor is cheap again, firms will not necessarily roll back these inventions,” said David Autor, an economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “These are kind of one-way transitions.”

That’s what worries union leaders. “In the auto industry, we see COVID accelerating transformation toward digitization,” said Georg Leutert, who heads the automotive and aerospace industries at Geneva-based IndustriALL Global Union. While the transition is unavoidable, workers are nervous and need help with up-skilling and re-skilling, he said.

Mark Lauritsen of the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union in North America said that in order to avoid the kind of disruption in the meat industry caused by the virus, automation will clearly continue but warned, “If automation is unbridled it’s going to be a threat.”

With office workers at home communicating via remote tools, a knock-on effect is also being felt: Bus drivers, sandwich stall owners and janitors are in trouble as their jobs, which support in-office work, diminish. Jobs in administrative support, which includes roles in office buildings, are down about 700,000 since last year, according to November data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The World Economic Forum reported in October that 43% of businesses surveyed are set to reduce their workforce due to technology integration while 34% plan to expand their workforce for the same reason.

Some argue that turning over repetitive jobs to robots will free up workers to take on new roles. But Marcus Casey, an economist at the University of Illinois at Chicago, said that while some high-skilled workers will be retrained, many low-skilled ones — like toll collectors — won’t, exacerbating inequality.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed