Alexander Deyev can still taste the smoke from last year’s wildfires that blanketed the towns near his home in southeastern Siberia, and he is dreading their return.

“It just felt like you couldn’t breathe at all,” said Deyev, 32, who lives in Irkutsk, a Siberian region along Lake Baikal, just north of the Mongolian border.

But already, this spring’s fires arrived earlier and with more ferocity, government officials have said. In the territory where Deyev lives, fires were three times larger in April than the year before. And the hot, dry summer lies ahead.

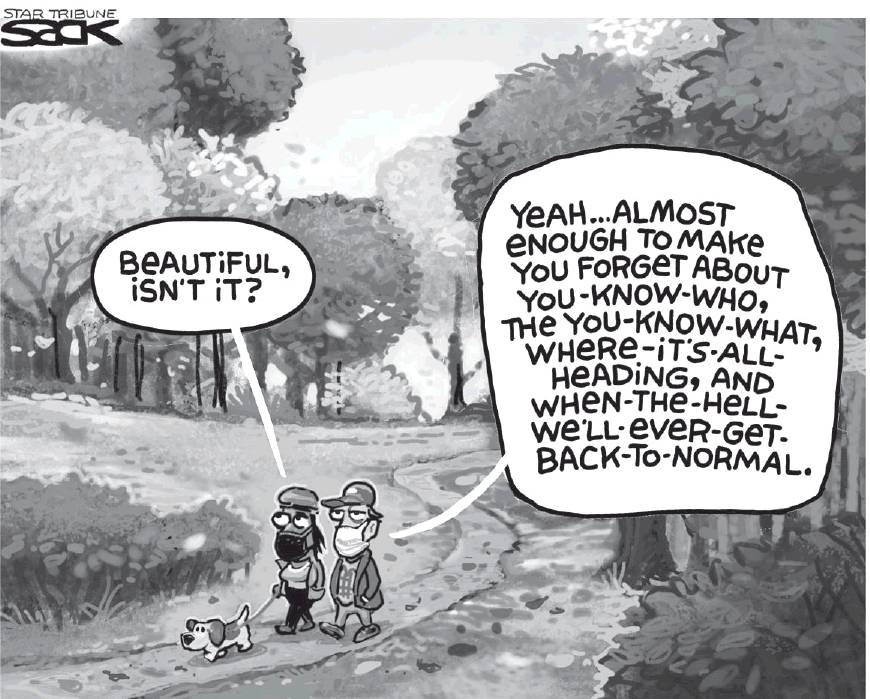

Much of the world remains consumed with the deadly novel coronavirus. The United States, crippled by the pandemic, is in the throes of a divisive presidential election and protests over racial inequality. But at the top of the globe, the Arctic is enduring its own summer of discontent.

Wildfires are raging amid record-breaking temperatures. Permafrost is thawing, infrastructure is crumbling and sea ice is dramatically vanishing.

In Siberia and across much of the Arctic, profound changes are unfolding more rapidly than scientists anticipated only a few years ago. Shifts that once seemed decades away are happening now, with potentially global implications.

“We always expected the Arctic to change faster than the rest of the globe,” said Walt Meier, a senior research scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado at Boulder. “But I don’t think anyone expected the changes to happen as fast as we are seeing them happen.”

Vladimir Romanovsky, a researcher at the University of Alaska at Fairbanks, said the pace, severity and extent of the changes are surprising even to many researchers who study the region for a living. Predictions that once seemed extreme for how quickly the Arctic would warm “underestimate what is going on in reality,” he said. The temperatures occurring in the High Arctic during the past 15 years were not predicted to occur for another 70 years, he said.

Neither Dallas nor Houston have hit 100 degrees yet this year, but in one of the coldest regions of the world, Siberia’s “Pole of Cold,” the mercury climbed to 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit on June 20.

If confirmed, the record-breaker in the remote Siberian town of Verkhoyansk, about 3,000 miles east of Moscow, would stand as the highest temperature in the Arctic since record-keeping began in 1885.

The triple-digit record was not a freak event, either, but instead part of a searing heat wave. Much of Siberia experienced an exceptionally mild winter, followed by a warmer-than-average spring, and has been among the most unusually warm regions of the world during 2020. During May, parts of Siberia saw an average monthly temperature that was a staggering 18 degrees Fahrenheit above average for the month, according to the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service.

The persistent warmth has helped to fuel wildfires, eviscerate sea ice, and destabilize homes and other buildings constructed on thawing permafrost.

Already, sea ice in the vicinity of Siberia is running at record low levels for any year dating to the start of the satellite era in 1979.

Scientists have long maintained that the Arctic is warming twice as fast as the rest of the world. But in reality, the region is now warming at nearly three times the global average. Data from NASA shows that since 1970, the Arctic has warmed by an average of 5.3 degrees, compared with the global average of 1.71 degrees during the same period.

This might seem like a distant problem to the rest of the world. But those who study the Arctic insist the rest of us should pay close attention.

“When we develop a fever, it’s a sign. It’s a warning sign that something is wrong and we stop and we take note,” said Merritt Turetsky, director of the Institute for Arctic and Alpine Research at the University of Colorado at Boulder. “Literally, the Arctic is on fire. It has a fever right now, and so it’s a good warning sign that we need to stop, take note and figure out what’s going on.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed