They suffered cracked ribs, two smashed spinal disks and multiple concussions. At least 81 members of the Capitol force and 65 members of the Metropolitan Police Department were injured, not even counting the officer killed that day or two others who later died by suicide. Some officers described it as worse than when they served in combat in Iraq.

And through it all, then-President Donald Trump served as the inspiration if not the catalyst. Even as he addressed a rally beforehand, supporters could be heard on the video responding to him by shouting, “Take the Capitol!” Then they talked about calling the president at the White House to report on what they had done. And at least one of his supporters read over a bullhorn one of the president’s angry tweets

“It was so obvious that only President Trump could end this. He was the only one.” Sen. Mitch McConnell

If nothing else, the Senate impeachment trial has served at least one purpose: It stitched together the most comprehensive and chilling account to date of last month’s deadly assault on the Capitol, shedding light on the biggest explosion of violence in the seat of Congress in two centuries. In the new details it revealed and the methodical, minute-by-minute assembly of known facts it presented, the trial proved revelatory for many Americans — even for some who lived through the events.

There were close calls and near misses as the invaders, some wearing military-style tactical gear, some carrying baseball bats or flagpoles or shields seized from the police, came just several dozen steps from the vice president and members of Congress. There was almost medieval-level physical combat captured in bodycam footage and the panicked voices of officers on police dispatch tapes calling for help. There were more overt signs about the coming violence from social media in the weeks leading up to Jan. 6 than many lawmakers had understood.

“Until we were preparing for this trial, I didn’t know the extent of many of these facts,” Rep. Madeleine Dean, D-Pa., one of the managers, told senators on Saturday. “I witnessed the horror, but I didn’t know. I didn’t know how deliberate the president’s planning was, how he had invested in it, how many times he incited his supporters with these lies, how carefully and consistently he incited them to violence on January the 6th.”

Yet for all the heart-pounding narrative of that day and the weeks leading up to it presented on the Senate floor, what was also striking after it was all over was how many questions remained unanswered on issues like the financing and leadership of the mob, the extent of the coordination with extremist groups, the breakdown in security and the failure in various quarters of the government to heed intelligence warnings of pending violence.

And then, most especially, what the president was doing in the hours that the Capitol was being ransacked, a point that briefly blew up the trial on Saturday.

The House managers were able to introduce a statement from a Republican congresswoman, Jaime Herrera Beutler of Washington, describing what she was told about a profanity-laden telephone call that Rep. Kevin McCarthy of California had with Trump in the middle of the attack.

Herrera Beutler said McCarthy, the House Republican leader, had told her that when he pleaded with the president for help , Trump seemed to side with the rioters disrupting the counting of the Electoral College votes ratifying his defeat. “I guess these people are more upset about the election than you are,” Trump told Mc Carthy in this telling.

The Trump camp has never provided an official account of the former president’s knowledge or actions during the attack. But advisers speaking on the condition of anonymity have told reporters that he was initially pleased, not disturbed, that his supporters had disrupted the election count and that he never reached out to Vice President Mike Pence to check on his safety even after Pence was evacuated from the Senate chamber.

Resisting pleas from Republican allies like McCarthy to explicitly call off the attack, Trump delivered a mixed message that day, embracing the rioters and endorsing their cause even as he called for peace and told them to go home. While one of his lawyers told the Senate on Friday that “at no point” was Trump informed that the vice president was in danger, that was contradicted by a phone call described by Sen. Tommy Tuberville, R-Ala.

Despite conflicting and sometimes fragmentary accounts, the House decided to proceed with impeachment and the trial without conducting a real investigation or calling witnesses .

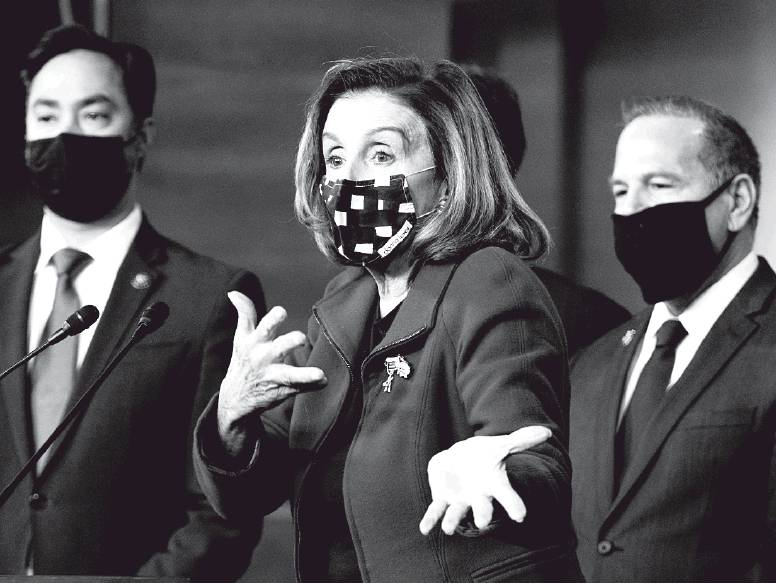

The managers concluded that the available record was compelling enough to make a judgment, but they have conceded gaps in their knowledge. “There’s a lot we don’t know yet about what happened that day,” Rep. Joaquin Castro, D-Texas, acknowledged at one point during the presentations.

The Trump defense team has sought to use that against the managers, arguing that they irresponsibly relied on unverified news reports and social media postings. “The House managers did zero investigation,” Michael van der Veen, one of the former president’s lawyers, said.

But the Trump lawyers evidently did little if any inquiry into their own client either, given that they were unable to respond to specific questions from senators about what the president knew and did during the rampage. And Trump rebuffed an invitation from the House managers to testify and clear up any confusion.

Even so, the presentations over the past five days clarified and framed the events of Jan. 6. The managers played Capitol security camera footage and police dispatch recordings while harvesting the enormous volume of videos and photographs posted on social media and other accounts by reporters, police officers, rioters, and members of Congress and their staffs.

Some of the senators learned for the first time just how close the attackers came to them.

Perhaps the most searing new details were audio and video recordings from police officers trying — and failing — to protect the Capitol. The radio communication became increasingly frantic, with one officer saying over a din in the background: “We have been outflanked and we’ve lost the line!” Another said: “They’re throwing metal poles at us!” They were attacked with bear spray and some sort of fireworks. One officer was dragged down a set of stairs; another was beaten after falling to the ground.

Managers documented as well the sheer scale of the desecration of the building itself. One worker had to clean feces off a wall. Another had to wipe up blood. And it was the sounds of that day that some remembered most vividly: the pounding on the door of the building, the crash as glass was smashed, the whispers of staff aides hiding from the crowd.

How much Trump was to blame for the onslaught was left to the Senate to decide. The defense team decried the House managers prosecuting the case for inflaming the senator-jurors with “manipulated video” that it argued proved only that the rioters committed crimes, not that the former president did.

Even then, the managers’ presentation brought home in emphatic fashion just how much some of the rioters thought they were acting on Trump’s behalf or even instruction, whether he knew it or not.

But what really struck some senators, particularly the handful of Republicans open to conviction, is what Trump did next — or what he did not do. Despite pleas from Mc Carthy, other allies, key aides and his daughter Ivanka Trump, the president was still more focused on pressing his effort to block the election than coming to the aid of his vice president and Congress.

When he called Tuberville, according to the House managers, he was not checking to see if he could help, but to re iterate his objections to the election vote process.

Until the trial, “I didn’t know … how many times [Trump] incited his supporters with these lies.” Rep. Madeleine Dean, D-Pa., one of the House impeachment managers

RSS Feed

RSS Feed